Are Registered Voters A Sample

The early days of a new presidential administration produce not but a blizzard of news but a blizzard of numbers. Pollsters of all stripes race to get and written report Americans' first impressions of their new president. But, frustratingly, those reports don't always match up as precisely as the Type A among u.s.a. might wish.

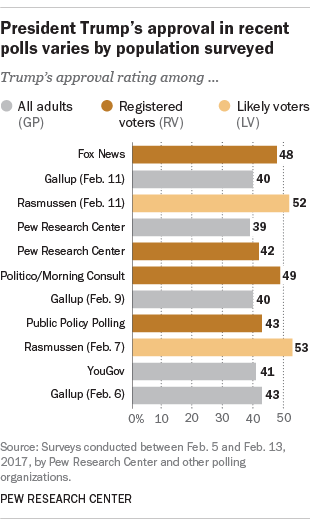

Take the by three weeks of polling on President Donald Trump. Depending on the poll, Trump's approval rating between February. 5 and xiii could accept been equally high as 53% or every bit depression equally 39%. So which was it?

In that location are a number of possible reasons for polls arriving at dissimilar estimates – from the fashion used to collect data to how people are selected for a survey – but here we'll tackle ane of the about basic: Did the poll include or exclude the 45% of adult Americans who didn't cast a vote last November?

Typically, polls in the U.S. are designed to stand for one of three populations. The broadest is the full general population of all adults (GP). Surveys based only on adults who are registered to vote (RV) use a narrower lens on the public. Narrower still is the filter applied with surveys that interview only registered voters who are deemed likely to vote (LV). Many pollsters might conduct surveys of all iii, depending on where they find themselves in the election bike.

Typically, polls in the U.S. are designed to stand for one of three populations. The broadest is the full general population of all adults (GP). Surveys based only on adults who are registered to vote (RV) use a narrower lens on the public. Narrower still is the filter applied with surveys that interview only registered voters who are deemed likely to vote (LV). Many pollsters might conduct surveys of all iii, depending on where they find themselves in the election bike.

In non-election years like this i, about pollsters survey all adults, but not all follow this convention. A number of pollsters continue to do surveys of registered or even likely voters. Why does this matter for Trump's approval ratings? It'south about demographics. Voters as a group skew older and whiter than the full general public. And older Americans, also equally white Americans, tilt more Republican than other groups. So, voter-only polls tend to get somewhat more favorable views of a Republican president or candidate and less favorable views of Democrats. This pattern was evident during Barack Obama's presidency, with his overall ratings tending to exist somewhat college among the general public than among registered or likely voters.

A await at some of the presidential approval numbers released this month shows a pattern consequent with these demographic differences. LV polls – those surveys based only on the views of "likely voters" – are generally reporting higher levels of support for Trump than full general population polls. There is a more muted just nonetheless significant difference in an RV-GP comparing: Pew Research Center's general population poll conducted February. 7-12 recorded Trump's presidential approval rating at 39%. Among registered voters in that survey, his rating was 42%.

Registered voter polls exclude near 40% of the population

And so how many people are we including, or excluding, when nosotros determine to expect at the views of only registered or likely voters? In the U.S., roughly six-in-ten adults are registered to vote. The registration charge per unit tends to tick up a few points in presidential election years (to well-nigh 65%) and back down a few points in non-ballot years. This means that RV polls, past design, exclude nearly 40% of adults living in the U.S.

LV polls, of course, exclude even more, every bit they aim to include simply those registered voters who actually cast, or will cast, a election. The voting rate among adults ages 18 and older was 55% in the 2016 presidential election and 33% in the almost recent midterm election. If a pollster is currently conducting an LV poll with 2018 (a midterm election year) in mind, and then recent midterm voting behavior suggests that their results might be excluding the views of a majority of adults in the U.S.

So what is the appropriate population to represent?

Which population is appropriate – all adults, registered voters or likely voters – depends on what data the poll is intended to gather. For political operatives whose jobs (winning elections) require them to be in perpetual campaign way, polls of registered or likely voters arguably provide the virtually accurate information virtually the mood and opinions of that subset of Americans who will actually cast a ballot in the next election. The fact that the poll excludes a large share of the population is a desired feature, not a bug.

For those interested in the opinions and experiences of the entire country, equally is the case hither at the Center, general population polls are a more than informative and useful tool. Nonvoters, similar any other group of Americans, include people who pay taxes, want health insurance, run pocket-sized businesses, utilise the public education or court systems and have a pale in the nation's security – even though they practice not play a role in selecting the officials who craft the public policies that affect them.

A last idea on nonvoters

While nonvoters do lean more Democratic than Republican, it would exist a error to cast them as a partisan lot. Overall, they are much less probable than registered adults to place with either major party (24% don't lean toward either political party, compared with 6% among voters). Then polls that exclude nonvoters don't just alter the shade of the state'south partisan balance, they paint a portrait of a public that is distinctly more politically engaged and ideological than those that survey all adults.

Correction: A previous version of this post and accompanying chart gave an incorrect figure for the Feb. 7 Rasmussen poll.

Claudia Deane is vice president of research at Pew Research Heart.

Are Registered Voters A Sample,

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/02/16/does-poll-include-or-exclude-nonvoters/

Posted by: sackettithersell.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Are Registered Voters A Sample"

Post a Comment